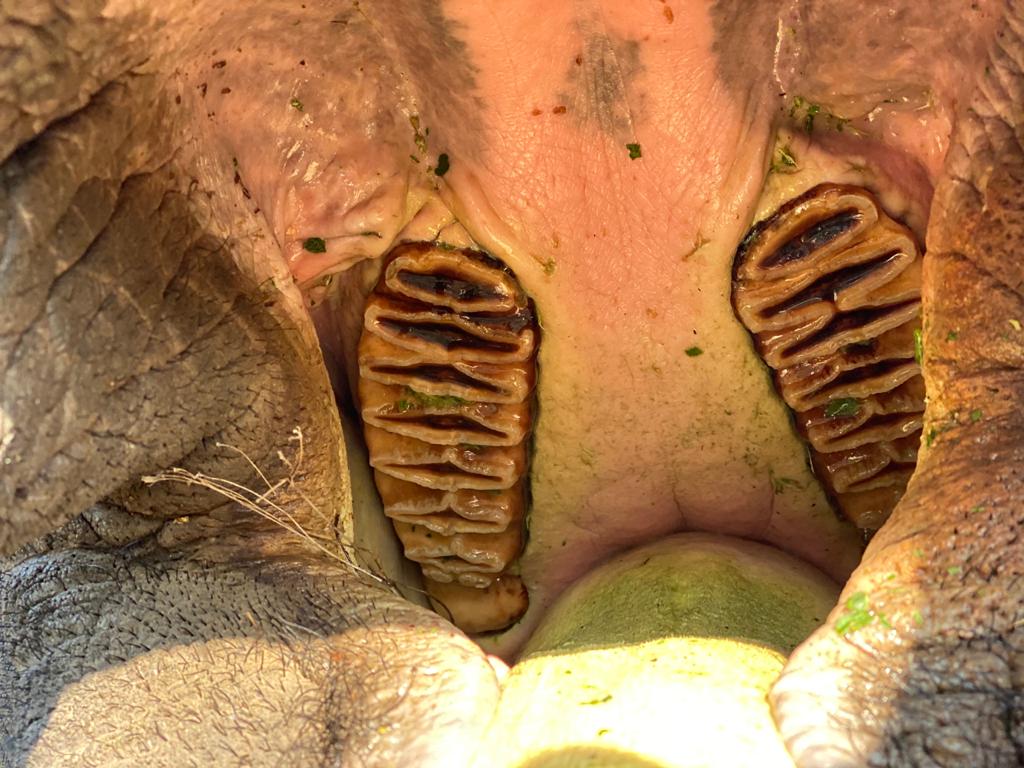

The Anatomy of an Elephant ~ The Elephant’s Mouth & Teeth

How did the elephant get its name? Well, it has something to do with their teeth. African elephants’ teeth are ‘loxadont’, meaning they are sloping. This characteristic gave rise to the species’ scientific name: Loxodonta africana, the African bush elephant, and Loxodonta cyclotis, the African forest elephant.

Asian elephant teeth are different, with a compressed diamond-shaped profile, to suit their diet and environment.

While for humans, teeth are produced from the top and bottom of the mouth, in elephants, they develop from the back and move forward. Elephants have only molars: with four at a time and one molar in each side of the top and bottom jaw. They are wide and flat in shape – perfect for grinding thick branches and grass for several hours a day.

During their lives, elephants go through six sets of molars and as a tooth wears out from all that grinding out in the wilderness, another molar pushes forward to replace it. In rare instances, an elephant may develop a seventh molar. Interestingly, manatees and kangaroos also have teeth that move forward in the jaw in this way.

When they are born, elephants have four small developing molars, which they lose at about two years of age. Each set of teeth thereafter lasts for a longer period of time until the final set, which arrives when they are around 30 – 40 years old. This set has to last them for the rest of their lives – which, in a protected wilderness like ours, can extend for 70 years. The teeth that are worn down eventually break off and fall out.

This loss of teeth is a leading cause of death among mature elephants. As the elephant’s final molar begins to smoothen and break down, it becomes increasingly difficult for it to chew and process food. This causes a decline in the animal’s well-being and many elephants die of starvation or malnutrition as a result.

Evolution is what led elephants to boast such special dentition, as their environments changed and they adapted “to sustain a long lifetime’s worth of heavy wear,” according to The Guardian.

Their trunks and tusks started to appear in their elephant ancestors by about 20 million years ago. “For a large animal with a short neck, the trunk was an extremely useful development, allowing these proboscideans to grasp leaves and bring them to the mouth, thus providing an evolutionary advantage.”

The development of a trunk and the transformation of incisors into tusks led to a change in the shape of the skull and, in turn, a change in the teeth. With their shorter jaw, elephants had less space for a full set of molars, but their teeth needed to be able to last them their whole lives.

Evolution’s solution: “Rather than having a whole set of premolars and molars crammed into the mouth at the same time – as in your mouth – there was just a single, large tooth occupying each side of the upper and lower jaw at any time. As this tooth wore down, another would be growing behind it, ready to slide into place when the worn-out tooth fell out, providing the animal with up to six sets of teeth in a lifetime.”

Next time you stare into the tomb-like mouths of Jabulani or Sebakwe or watch a wild elephant feeding in the wild, remember just how much work and purposeful intention (on nature’s part) went into the creation of their vital and fascinating tools.

What else is happening in the mouth? Two very important things… The tusks and the Jacobson organ. Read about them in our blogs.

Watch Our Videos

Susan

I love that their teeth look like Christmas ribbon candy - beautiful structure. Wonderful video & I learned so much. Thank you. And, I loved the closeup of Khanyisa eating... just fascinating watching her little tongue maneuver the dry branches back to the side where her teeth can chew them. It's sad these strong teeth which chew the food to give them nutrients to sustain them throughout their lives ultimately will fail them later on and cause what is likely, or possibly, a painful death. It's so heartbreaking to think of them starving & getting weaker, only to collapse & lie there alone & vulnerable in the heat & sun until their breath finally leaves them (or worse, they are attacked). But, in fact, humans often reduce their eating to nearly nothing at the end stage; they sleep a lot until they leave us. I guess it is similar with elephants. Many thanks, again.

Judith

Fascinating! Thank you for taking the time for explaining their eating habits. Alway exciting to lean something new. I am dedicated fan of HERD!

Jeanne Torma

Thanks for this interesting and informative information, I really appreciate your do so.