Stop Snaring | A Threat to Wildlife Around the World

Today is World Wildlife Day, a day dedicated to celebrating and raising awareness for the wild animals and plants we share this planet with. Wild animals and plants face many threats, and several species are at risk of becoming extinct, including elephants. One threat that is having an increasing impact on wildlife, not only in South Africa, but around the world, is snaring.

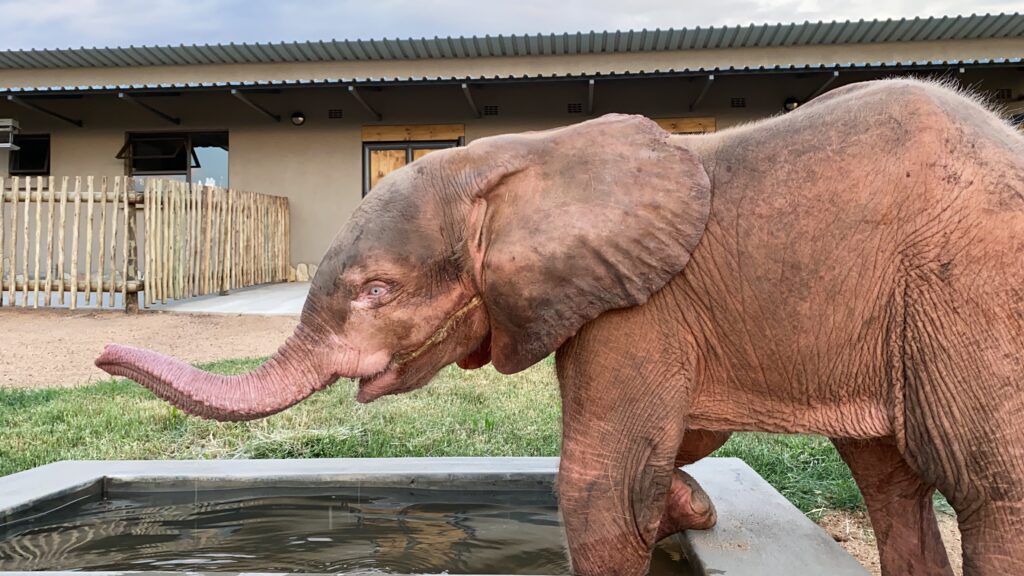

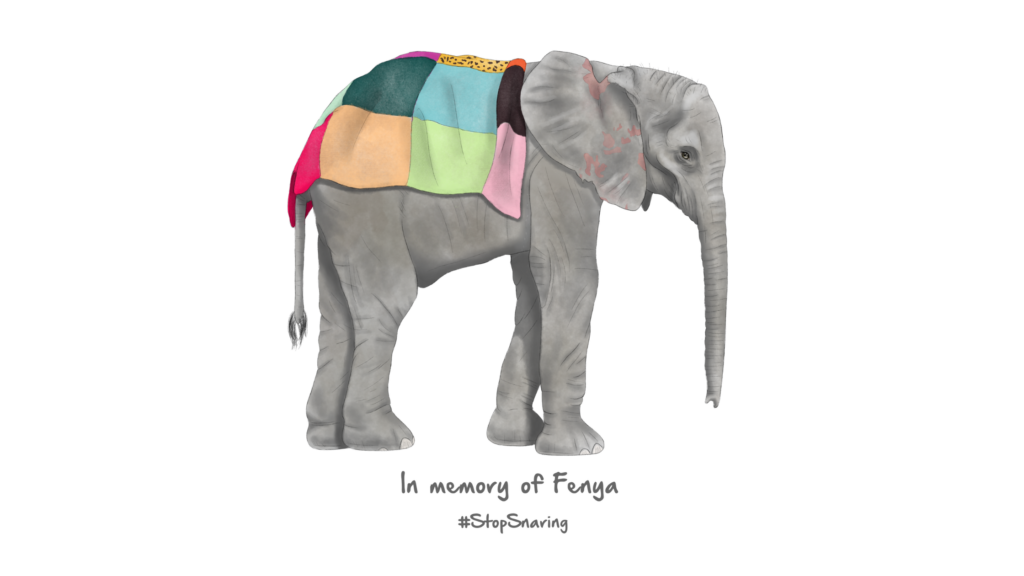

At HERD, we are all too familiar with the threat of snaring. The youngest member of the Jabulani elephant herd, Khanyisa, was rescued from a snare in 2020. In 2021, elephant calf Fenya was rescued from a snare, but she succumbed to the injuries she had sustained while being trapped in the snare. Soon after her death, we launched our #StopSnaring campaign to raise awareness of snaring. Now, in 2023, snare hunting is on the rise. In its last annual report, South African National Parks (SANParks) reported that the number of snares that had been removed from national parks during the previous year had doubled from the year before.

In this blog, we look at what snaring is, why people snare animals, why snaring isn’t sustainable, and how snaring can be stopped.

Note: Snaring is a complicated issue. We try our best to explain snaring, its causes, and its solutions in this blog, but we cannot touch on every aspect of snaring in just one blog. You can find links to more information on snaring in the sources section at the end of the blog.

What exactly is snaring?

Snaring refers to the act of hunting animals by using a snare. A snare consists of a noose on one end and is attached to a heavy or immovable object on the other end. When an animal steps on or tries to walk through a snare, the noose tightens around the animal’s neck, body or limb. The harder the animal pulls against the snare, the tighter the noose becomes. The animal is trapped in the snare, anchored to the object the snare is attached to.

Why are snares so popular?

Snaring is a popular method of hunting for a number of reasons. As Laurel Neme explains in an article for Mongabay, snares “hit the hunting trifecta: They’re cheap, effective, and made from easily available materials, like rope, wire or brake cables.” Snares are also easy to set, and a single person can set a very large number of snares in a short time.

Where are snares placed and used?

Snares are placed in areas that animals are known to move through. The organisation Snare Aware provides training around South Africa on how to identify and remove snares. Their list of ‘Snare Sweeping Principles’ gives valuable insight into where snares are often placed. When the team searches for snares, they look for the following:

- A wildlife trail. The Snare Aware team explains that this is the first thing they look for when searching for snares.

- Signs of movement (human or wildlife) on the trail.

- A natural ‘choke point’ or ‘anchor point’ on the trail where wildlife will naturally be funnelled. Snare Aware explains that “this is where the path either goes under a natural ‘tunnel’ of vegetation or into a patch of bush (clear entry/exit point) forming a natural choke point.” The team also looks for where the trail passes tree branches, as these provide optimal places to anchor a snare.

- Artificial manipulation of the bush. “Where a natural choke or anchor point does not exist,” Snare Aware explains, “the poacher will manipulate the bush to create one. This includes cutting, bending, or manipulating branches to create choke points and block off alternative pathways to funnel wildlife to their trap.”

- Trees with appropriate stem diameter. Snare Aware explains that “poachers don’t waste material on thick branches or stems, and stems that are too small do not provide the necessary strength to contain a panicking animal.”

- Anchor points on the stems or branches, and stabilisation sticks. “The stabilisation sticks are often used (but not always) to prop up the noose of the snare,” Snare Aware explains. “Two straight sticks are cut and spliced, then placed in the ground on either side of the noose to prop it up. The noose is placed within the splice on the top of the stick.”

What happens to an animal caught in a snare?

An animal caught in a snare is either found by the person who set the snare and is killed, or the animal dies before they are found. Snares aren’t always checked regularly and many snares are never checked at all. A World Wildlife Fund (WWF) report on snaring states that snaring is considered to be a cruel method of hunting, as animals caught in snares “can sometimes languish for days or weeks in a snare before dying from their injuries, dehydration or from starvation.”

Snares don’t always work as planned and sometimes animals may escape from snares by detaching the snare from the object it’s attached to. However, an animal won’t be able to remove the noose of a snare, and it will continue to pose a serious threat to the animal. The major injury caused by the snare may lead to infection or the loss of a limb. Depending on where on the body the noose has tightened, it may make it difficult or impossible for the animal to eat, drink, breathe, or walk. Eventually, it almost always leads to death.

Why do people snare animals?

It is important to separate the different reasons for the illegal hunting of animals – also called poaching. The most well-known reason for illegal hunting is to sell body parts of animals, such as elephants’ tusks or rhinos’ horns. This type of poaching tends to be highly organised and is not done by individuals, and snaring is not believed to be a favoured method of these poachers. Rather, snaring is believed to be a preferred method of those hunting for bushmeat.

The term bushmeat refers to the meat of wild animals. Bushmeat hunting is affected by several socio-economic factors, and the drivers of bushmeat hunting vary between different areas and different people. For many rural communities, such as those situated next to nature reserves, bushmeat serves as a valuable source of protein and income. Nature reserves are often situated far away from cities and large towns, and as a result the communities situated next to them tend to be reliant on the reserves for jobs and economic growth. But reserves can only employ a limited number of people, and reserves don’t always have the methods, resources or means to provide other benefits to the communities that rely on them. With very few economic opportunities available to the people living in these communities, many live in poverty. Some may turn to bushmeat for food or income. As Peter Lindsey, the director of the Lion Recovery Fund Wildlife Conservation Network, explains to Mongabay: “In most parts of Africa, mechanisms to benefit communities from wildlife are not really there, so they take the only benefit that is available to them, which is to hunt for the pot or hunt to sell.” Some people may hunt for bushmeat purely to feed their families, while others may do so to sell the meat. Often times, people do it for a combination of these reasons.

In some cases, bushmeat hunting may be more commercial. Bushmeat is popular in some urban areas, where it may be sold in markets or restaurants. These urban bushmeat industries therefore fund rural bushmeat hunting, leading to widespread and large-scale snare hunting. In some areas, the demand for bushmeat from urban consumers appears to be increasing.

What are the consequences of snaring?

Modern snares are easier, cheaper, and faster to use than traditional hunting methods, and they therefore have a much bigger impact on wildlife and the environment. Bushmeat hunting has been around for as long as humans have, but modern hunting methods and the large number of people who now hunt mean it is no longer a sustainable way of hunting for food. As Peter Lindsey explains: “The challenge is that while bushmeat hunting has been done since time immemorial, the number of people [doing it] has increased dramatically while the wildlife resources have declined drastically — so the demand for bushmeat relative to the supply is enormous.” Today, conservationists consider bushmeat hunting to be a serious and immediate threat to wildlife. Furthermore, species decline caused by bushmeat hunting will ultimately also negatively affect the very communities that currently rely on it, and will eventually threaten their food security.

Though hunters may target specific species, snares are indiscriminate and non-target species are just as likely to be caught in them as target species. Endangered or threatened species are therefore also often caught in snares. Many of the animals that are frequently caught in snares contribute greatly to the ecosystems they live in, and the decline of their numbers therefore have negative impacts on their ecosystems. These animals include ones that disperse seeds, ones that control population sizes of prey species, and ones that act as ecosystem engineers. If these animals are no longer able to sufficiently provide the ecosystem services that their environments rely on, it can have far-reaching consequences such as plant extinction, crop damage, overgrazing, reduced carbon storage, reduced biodiversity, increased soil erosion, and increased frequency of wildfires.

Another risk that comes with snaring and the handling of wildlife and bushmeat is the increased exposure to zoonotic diseases – diseases caused by a pathogen spreading from an animal host to a human. Snaring itself involves close contact with wild animals, and the risk of zoonotic diseases developing increases when animals or carcasses are stored or transported with other animals or carcasses. Zoonotic diseases can have devastating effects on communities and the entire world – as was recently seen with the Covid-19 pandemic.

What can be done to stop snaring?

Snaring is a complicated issue and therefore potential solutions to snaring are just as complicated. There is no single way to stop snaring, and what works in one region may not work in another. In order to stop snaring, the situation in each region needs to be evaluated and a variety of different solutions need to be implemented. We cannot explain all potential solutions to snaring in one blog, but we’ll focus on three important aspects of stopping snaring: engaging with and involving local communities, reducing demand for bushmeat and changing behaviour, and implementing effective anti-snaring laws and law enforcement.

It is important to remember that no solutions to snaring can be found, or should be implemented, without engaging with and involving the communities situated next to nature reserves. Many conservation organisations have emphasised the importance of involving communities in conservation. The WWF, for example, recommends that groups aiming to stop snaring should “organise formal meetings and dialogues with local communities, with the goal of creating mutual agreements and strategies to combat snaring and other wildlife or environmental crimes.” They also recommend that local community members be employed in projects that aim to reduce snaring.

Another important aspect of stopping snaring is reducing the demand for bushmeat. One way of doing this is through education on the negative effects of snaring, not only on wildlife and the environment, but also on humans. Some anti-snaring campaigns, for example, focus on the risk of zoonotic disease that comes with bushmeat hunting and eating. Such campaigns are often also aimed at those in urban areas that consume bushmeat, but do not hunt for bushmeat themselves. As there are many people who are reliant on bushmeat hunting for protein and income, alternative sources of protein and income would need to be provided for these groups. Such alternatives, such as agriculture and raising livestock, are often costly and come with their own risks. There are many factors that need to be taken into account when looking into alternatives, and what works for one community will not necessarily work for another. Reducing the demand for bushmeat will require time, resources, and funding, but it is necessary in order to stop snaring.

Effective anti-snaring laws and law enforcement are also crucial aspects of stopping snaring. Anti-snaring laws aim to deter hunters from using snares, either by use of fines or jail sentences. These laws should be strict enough to be effective. These laws should ideally not only apply to those caught in the act of snaring, but also to those who are in possession of snares or snare materials in protected areas, and possibly even in areas that border protected areas. Ranger patrols are necessary to prevent the setting of new snares and to remove snares that have already been set. As snares are difficult to detect, ranger patrol coverage and frequency need to be sufficient, and rangers need to be trained to identify snares.

In some areas, volunteers take on the responsibility of finding and removing snares. Snare Aware, for example, regularly searches for snares in protected areas and responds to reports of snaring activity from community members. The Snare Aware team believes that a regular and persistent presence in snaring hotspots deters poachers, and they have reported decreased snaring activity in areas that they regularly search. “Despite many doubters telling us that we are wasting our time and that the snares will be replaced quicker than we can remove them, we have shown that through persistence and perseverance, and by creating presence, we can deter, slow down and even eliminate poaching,” the team states.

Sources

Belecky, M., Gray, T.N.E. (2020) Silence of the Snares: Southeast Asia’s Snaring Crisis, WWF International. Available at: https://files.worldwildlife.org/wwfcmsprod/files/Publication/file/dndcz1okh_Southeast_Asia_Snaring_Crisis_WWF_9July2020_V2_LowRes.pdf.

Lindsey, P., Taylor, W.A., Nyirenda, V., Barnes, J. (2015) Bushmeat, wildlife-based economies, food security and conservation: Insights into the ecological and social impacts of the bushmeat trade in African savannahs, FAO/Panthera/Zoological Society of London/SULi Report. Available at: https://www.fao.org/3/bc610e/bc610e.pdf.

Neme, L. (2022) ‘Snares: Low-tech, low-profile killers of rare wildlife the world over’, Mongabay, 18 August. Available at: https://news.mongabay.com/2022/08/snares-low-tech-low-profile-killers-of-rare-wildlife-the-world-over/.

SANParks (2022) SANParks Annual Report 2021/2. Available at: https://www.sanparks.org/assets/docs/general/annual-report-2022.pdf.

Secretariat of the Convention on Biological Diversity (2011) ‘Livelihood alternatives for the unsustainable use of bushmeat’, report prepared for the CBD Bushmeat Liaison Group, Technical Series, No. 60. Available at: https://www.traffic.org/site/assets/files/2678/alternatives_for_unsustainble_bushmeat_report.pdf.

Tan, J. (2020) ‘Bushmeat hunting: The greatest threat to Africa’s wildlife?’, Mongabay, 26 October. Available at: https://news.mongabay.com/2020/10/bushmeat-hunting-the-greatest-threat-to-africas-wildlife/.

Special Mention

We are immensely grateful for Snare Aware for allowing us to share their information and images in this blog. You can learn more about snaring and the valuable work that Snare Aware does on their Facebook and Instagram accounts.

Sharon Fastnaught

Informative and heartbreaking. Knowing all this is important, but it saddens me in so many ways. I discovered HERD after Fenya but have followed them ever since. I wish we lived in a world where such things didn't happen. Until then, I am thankful to have HERD and other groups advocating for the animals. Supporting HERD was an easy choice.

El pirata

through the various YouTube channels i folllow I have had the misfortune of seeing the sickening effects of traps and snares unleashed on these unfortunate critters. missing all sorts of body parts. this is heartbreaking to watch and misery for these creatures. then I think how sick this world makes me. the pain and suffering we humans infflict on our fellow creatures is wrong. when does it stop? why don't we as humans understand pain is something we all share.